The car was parked alongside a dub-shod and dented Cadillac Seville, and some ravaged F-series pickups. All the vehicles had "For Sale" signs displayed or, in the case of the trucks, had been lazily tagged as such with smears of red across their windshields in paint that may have been (but probably was not) washable.

I involuntary jumped up in my seat and yelped as soon as I saw this car, behavior which warranted an explanation to my boss, who was driving.

We had just come from a site meeting with a contractor who seemed doubtful about the prospects for the renovation of the house in question. He wasn't alone. The architect had once almost involuntary breathed "God, I hate that house" into the phone during an conversation we had to confirm the location of a six-inch offset that zig-zagged through the floor in the middle of the structure, a demarcation of the ungraceful hand-off in the foundation from slab-on-grade to piered-footings.

The proposed renovations, like any, would leave the building with a haphazard collection of these irritating and inexplicable vestiges of the original design limitations, and the appended, grandiose monuments to conspicuous consumption. In this case, the latter included an artificial beach on the rear deck and a prominent entry vestibule, containing four stories of stairs, cantilevering proudly from the walls, granting the owner membership to the very exclusive club of people who could very easily fall to their deaths within the confines of their own homes.

It's a poorly kept secret of the construction industry that cost and potential for a catastrophe is disproportionately high when you compare renovation or restoration to new construction. A good rule of thumb is this: if you're thinking of repainting the bathroom, just fucking tear the house down and start from scratch. You'll live longer.

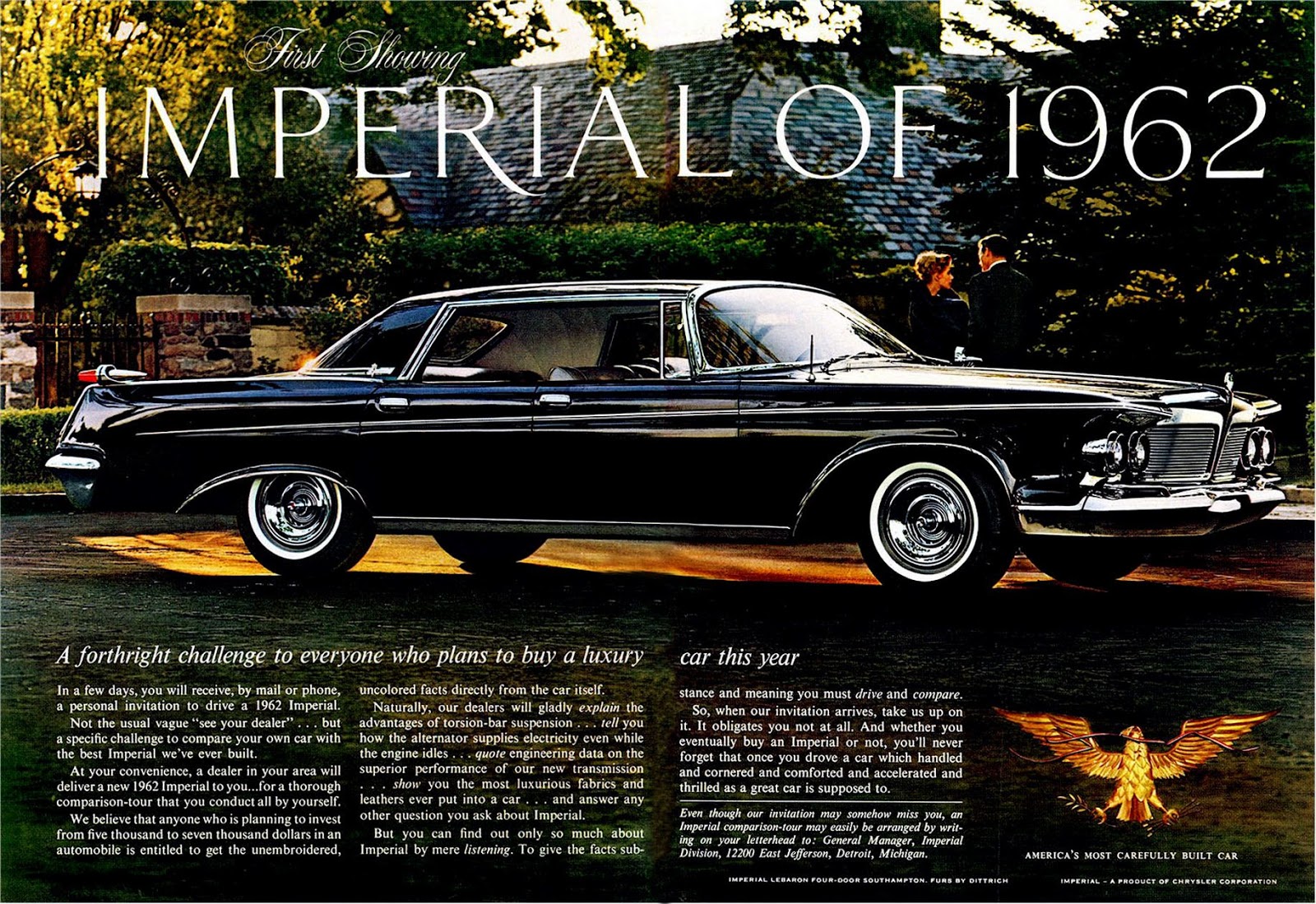

Perhaps it's good that these were the types of things I was thinking about when I saw this car, which was a 1962 Imperial, the very car I've always lusted after in the fantasy world of, "what would be the absolute coolest fucking car to own, ignoring scarcity, price or practicality." This might sound like an oddly-restrictive category, but this is a totally normal thing for car-folks; and how we each manage to have about 16 "favorite cars."

Although my impulse was to demand that my boss turn around immediately and head back, I was able to quell the feeling and return after work, driving an hour in the opposite direction from my house, intending to snap a few photographs and make some inquiries, which I did. It took me a long time to pull myself away, and I spent that time trying to figure out why this car feels so important to me.

Although, it's not universally reviled among car stylist folks, it's certainly not a favorite--as far as I can tell because its design philosophy was a few years behind the times.

Which should make perfect sense, really. This is a car designed by the man who was arguably (and people really do argue about this) more responsible than any other single human for the trajectory of auto design during the 1950's, Virgil Maximilian Exner, Sr. a man whose name sounds as ornate, overwrought, and as vaguely Gothic as this Imperial looks. When the '62 went to market, he was no longer lead designer of Chrysler, marking the end of his career within the mass-market big-three. The world had moved on, so this would be the first in a series of orphaned Imperials, several years of gestural attempts to freshen Exner's swansong 1961 design, which basically looks like this one (but with giant fucking tail-fins, already embarrassingly out of fashion when it was launched).

And I'm pretty sure that this was the last "off-the-rack" car ever made with free-standing head-lamps. As the overall automotive shape was evolving toward the rectilinear slab, this treatment required deep scallops on either side of the frontal fascia, starting just outside the grille. Although this might be seen as one of the more needlessly pompous design features, I think it's just stunning--and not an insane choice, considering that there was nothing but wasted space behind the headlamps anyway. Aerodynamically, I can't imagine it makes any difference one way or the other, so the only real drawback is that it's horribly expensive to do something that looks this good. A bit garish though? Duh.

And I'm pretty sure that this was the last "off-the-rack" car ever made with free-standing head-lamps. As the overall automotive shape was evolving toward the rectilinear slab, this treatment required deep scallops on either side of the frontal fascia, starting just outside the grille. Although this might be seen as one of the more needlessly pompous design features, I think it's just stunning--and not an insane choice, considering that there was nothing but wasted space behind the headlamps anyway. Aerodynamically, I can't imagine it makes any difference one way or the other, so the only real drawback is that it's horribly expensive to do something that looks this good. A bit garish though? Duh.

Nothing about 1950's America was subtle, functional or remotely well-thought out--and neither is anything on this car. Which is why I really don't understand critiques that bill Exner's work as especially excessive or farcical. That was the whole postwar zeitgeist right there. Looking back, it's hard to argue that anything from the period doesn't fit that description in the grand scheme of things. Parked next to one of these, the iconic and lauded 1957 Chevrolet looks just as tasteless in its design goals, but not nearly so majestic.

Yes, just about everything that speaks to the failed promise of the jet-age is represented in this specimen, only taken to their logical conclusions--this was a conveyance created as wastefully-large and as gizmo-laden as we, as a country, could muster. For example, the transmission was operated without big, clunky levers, rather gears were selected with discreet electronics, like in a Toyota Prius. If you think this sounds odd, because you assumed that we hadn't quite mastered that technology by 1962, you're quite right. Oh, it didn't "work" exactly, but wouldn't it have been cool if it did? If only it were powered by self-assured swagger. And 1962 is often cited as the year that American's endless optimism started to seem a bit...ill-conceived? There was the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Bay of Pigs invasion, and things were not looking good in Vietnam. Everything was in violent flux, and the entire character of this car--even its very name seemed to hearken back to an era long forgotten. Check out this super-sexist product info reel which doesn't address a single technical issue.

The Imperial was a catastrophic failure in sales and build quality, but in its failure, it is confident, magnificent--dare I say--righteous? Yes. Righteous in its failure. Which is exactly why I think of it as the most American car ever built.

Personally, I think it's exactly because Chrysler was always the company a decade late and a billion dollars short that their products seem so compelling in terms of narrative; they're distant history even as they're coming off the assembly-line and disappearing into the endless acres of rolling abortions, making them especially useful in identifying the markers that will define an era; reminding us of what we are not.

For this reason, I think the story of the entire American auto industry (which is equal parts comedy and tragedy) is told best by Chrysler. Which is to say, they invariably fare the worst whenever something bad happens.

Another favorite example of mine is undignified euthanasia of the all the old-school American marques. We usually think of the day when the General pulled the plug on Oldsmobile--a muted affair to be sure which garnered very limited press; principally interviews with a few old codgers showing off their 442's and giving the outgoing Aurora a nice send off. But the demise of Plymouth I find much more emblematic of this phenomenon, because of the fact Chrysler had relegated the brand to indistinguishable re-badges for so long that no one even noticed when they dragged it out to the barn and put the poor thing out of its misery. And this really is the worst case scenario in brand-death, having passed so many years nearly dead, without any signs indicative of the presence of a cohesive soul--or for that matter seemingly any rational human intelligence pulling the strings. I don't think I'm the only one who finds this scenario evoking the fear that my own decline into dementia will be so gradual, that my (theoretical) kids don't even give a shit when I die.

But I digress.

...

I did find the owner, and I did ask the price. In truth, even though it would have been really difficult to scrounge up the cash, I could have made it happen. But I didn't.

But I digress.

...

I did find the owner, and I did ask the price. In truth, even though it would have been really difficult to scrounge up the cash, I could have made it happen. But I didn't.

The reason I walked away was that I knew, beyond any reasonable doubt that this project would become the fact that defined my entire life for a period of time beyond reckoning.

As someone who grew up surrounded by projects that had silently rotted, and imperceptibly turned into monuments of neglect and failure, I knew that no good would come from this.

A few weeks have gone by now, and I think about the Chrysler sometimes, especially when I'm working on a renovation project that is probably doomed, which is quite a lot.

Unfortunately, we are curious and hopeful creatures. Even though I knew that I had made the right decision, I also knew that I would never get the chance again, that I would never again come across my specific ideal, and certainly not find it in such perfect, unmolested condition.

Occasionally, it's easy to see that our dreams are completely impossible, but some folks have to sink tens of thousands of dollars into a project before their own recognition scene. One thing I can tell you: as far as I can work out, there isn't a "no regret" option.

No comments:

Post a Comment