But they do, and consequently, one doesn't.

I never thought I'd buy a GM product. In fact, back in high-school, had I been forced to wager what particular model I would never own, the H-platform Buick LeSabre would certainly have been a contender. A friend's step-father drove one of these things. He was the only real-live person I've ever heard say the phrase "there is no replacement for displacement" in full sincerity. But, his bulbous Buick seemed disprove his theory in reverse (or maybe in inverse..obverse?) The 3.8 liter engine made a comical 170 brake horsepower, which would be okay for an engine roughly half that size. I'm still more than a little amazed that GM managed to coax so few horses out of such a capacious barn. In my mind, the car was a product specifically built for a consumer who either hated cars outright, or else understood nothing about them: the automotive equivalent of The Dave Matthews Band. But things change. And the years have been surprisingly kind to this low-rung Buick.

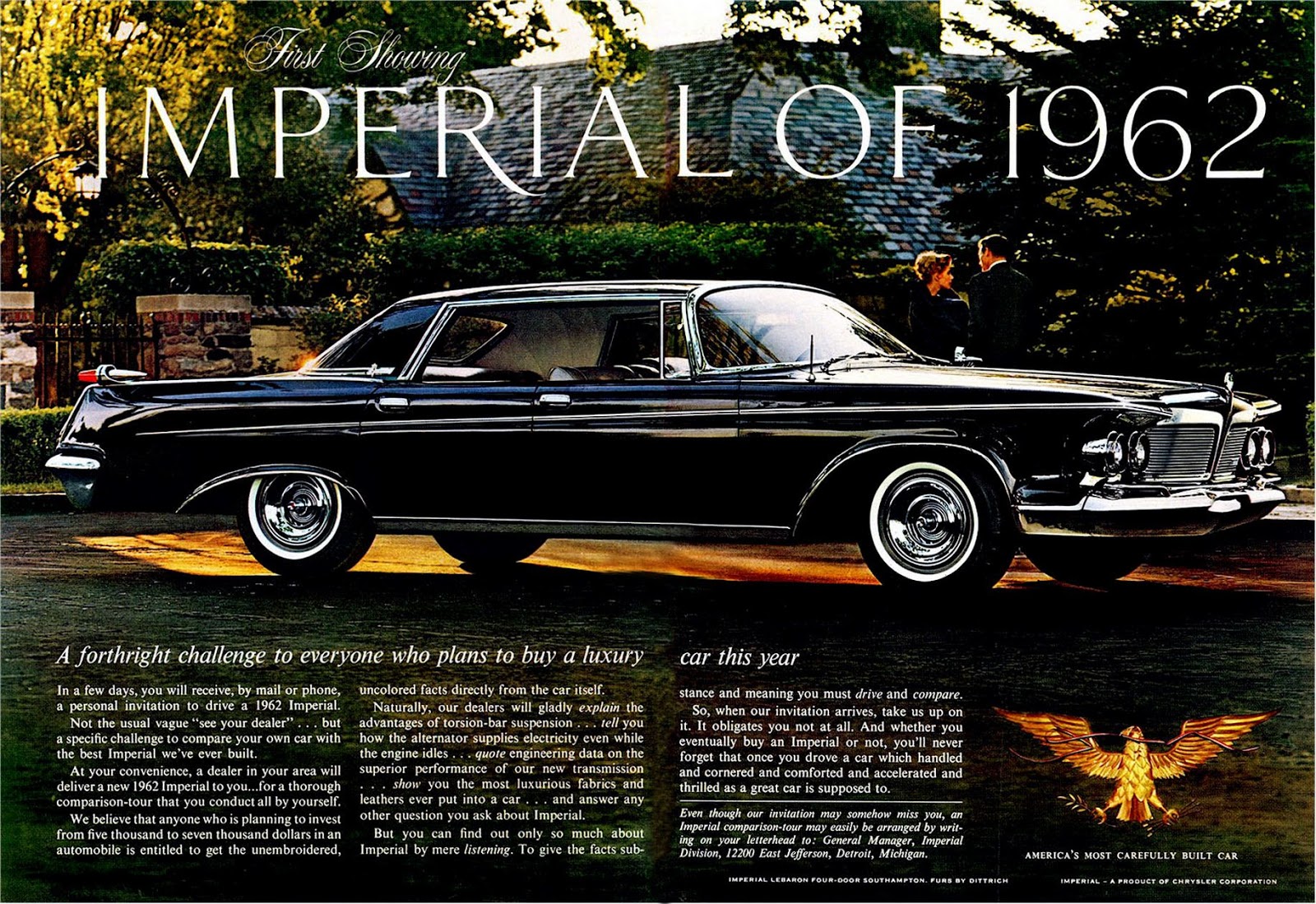

|

| This is called "curb-appeal," folks |

I never thought I'd buy a GM product. In fact, back in high-school, had I been forced to wager what particular model I would never own, the H-platform Buick LeSabre would certainly have been a contender. A friend's step-father drove one of these things. He was the only real-live person I've ever heard say the phrase "there is no replacement for displacement" in full sincerity. But, his bulbous Buick seemed disprove his theory in reverse (or maybe in inverse..obverse?) The 3.8 liter engine made a comical 170 brake horsepower, which would be okay for an engine roughly half that size. I'm still more than a little amazed that GM managed to coax so few horses out of such a capacious barn. In my mind, the car was a product specifically built for a consumer who either hated cars outright, or else understood nothing about them: the automotive equivalent of The Dave Matthews Band. But things change. And the years have been surprisingly kind to this low-rung Buick.

Durability: 8/10

This specimen sputtered to life in Flint, Michigan, some five years after Micheal Moore released "Roger and Me," his least fictional and most compelling documentary to date. One of the larger narratives he did skip in the film, was the precipitous decline in quality that plagued the US auto industry. The fact that, at this time, we Americans had irrefutably earned the reputation for building the most catastrophically-ill-conceived, haphazardly-assembled, and basically undriveable embarrassments ever to sully our roads (which aren't so impressive, themselves).

Which was why I was surprised to see so many Buick's running around Texas--. Back in 1990's California, if you wanted to buy something as comfortable, conservative and unpretentious as a Buick you just went to your Toyota dealership and got a Camry or the tarted-up Lexus version. (Actually, if you're in the camp that considers the state an economic prophet/canary for the rest of the US, it won't surprise you that around this time all the middle rungs of GM's price ladder pretty much got slaughtered in CA).

Apparently though, in the regions we now call "red-state America," folks were not as disgusted by GM's atrocious quality control record, or their embarrassingly shitty marketing, so they continued to buy LeSabre's, Bonneville's and 98's instead. And despite what we thought at the time, these H-platform cars proved damned hard to kill. Don't get me wrong--the first year data from JD Power and Consumer Reports are all well and good, but for someone like me, who typically owns cars in the twilight of their...existence, the real numbers are sourced from how many you see on the road once they've reached the age and mileage that place them in a state of chronic neglect and abuse. And a shocking number of these bread-n-butter, full-sized boats are still stubbornly clinging to life, scuttling about like giant, rusty cockroaches, more than likely delivering your pizzas and your drugs.

|

| Wheel covers went straight in the trash, obviously. |

Performance: 1/10

To be fair, all the roads in Texas are miserable, traffic-clogged straightaways, specifically designed for sloppy barges like this, so the point is all but moot. If you actually find a corner, and try to hustle the Buick around it, you will find that it delivers all the drama of of Hollywood car-chase, with screeching tires, wallowing suspension and a roaring, push-rod engine note--sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Here's something: you know that moment, when a light turns yellow at just the wrong time, when normally you would think, "Should I accelerate across, or should I stop?" This car doesn't have either of those options. The question becomes "I wonder if it will be worse to be going 5 mph slower, or 5 mph faster when this light turns red?" That's literally all you can do.

I do appreciate that the General ponied-up for Anti-lock brakes as standard equipment, but adding ABS to a car with suspension this soft and poorly controlled seems like a very expensive and roundabout way to address the issue--and yet manages to leave it not quite solved. Like building a house out of--I dunno--frozen caviar. There are simpler solutions.

Although the car is under-powered, people tend to get out of the way when you're coming up behind them at speed, presumably thinking the thing is being piloted by an oblivious octogenarian who has confused the throttle with the brake, and is on his way to mow down a whole field of marathon runners.

|

| Quarter mile time? You know I'm fucking majestic, right? |

Passenger Room: 10/10

It's really too bad that the power lock mechanism is broken on the passenger side, because the bench is so wide, I have to lay flat across and stretch the tippy-tip of my middle finger out to unlock it manually.

|

| You're reading that correctly. |

In fact, the width of this car is such that I have been robbed my of one of my favorite highway pastimes; this first-world problem snuck up on me, guys.

Cargo Volume: 7/10

By most metrics, trunk size would be considered more than adequate here. Popular opinion holds that trunk volume must be assessed as an integer value measured in dead hookers, (If you find this misogynistic, please remember that hookers can be any sex or gender. You bigot.) I'd say this trunk could probably fit about 3 hookers, depending on what body-type you're into. Unfortunately, the space just isn't as flexible as that of a station wagon or roof rack. Also, not nearly so comfortable.

|

| And way more exhaust fumes. |

Character: 9/10

The worst thing about the car market today (or at least the thing that I complain about most) is the oppressive sameness that has engulfed everything over the last decade or so. Oh, sure, things work much "better," but I really miss the specificity of character that used to exist between brands. Not so long ago, the European, Japanese and American industries had distinct, unmistakable DNA. When I was growing up, everything from Japan looked like a transformer and had totally incoherent marketing. European cars were as remote and as chillingly-bourgeois as an ascot worn in earnest. And American "luxury"cars like this one had the character of ignorant (but well-intentioned) bucktoothed hillbillies, wearing clip-on bow-ties. In short, they were like us.

Better always meant, simply, "more." Clearly, this was the philosophy that pervaded every design meeting in Detroit.

Do your toddlers smoke? Fuck it. Of course they do. Everyone gets an ashtray in the armrest. Four ashtrays. Why not? Done and done.

Also, six sun-visors. No--four isn't enough, asshole--what if there are TWO suns, one shining on either side of the car, and then a helicopter pops up over the horizon with that spotlight in your face--'cause also, it's at night--then what, smart-guy? Six visors.

And so on.

|

The result is a car that evokes the feeling of a 1970's suburban living room, dark and smokey, with expansive velour furniture and a charming selection of hard plastics, printed in a mockery of natural wood-grain.

Basically, it's so fucking obsolete, it's absurd. But that's okay.

I remember watching some motoring show years back, that featured a Japanese Buddhist monk who drove a 1908 Bentley something-or-other. Placing collector value momentarily aside, the host asked why he chose such a punishing and out-of-date conveyance as his main vehicle. The monk said that the syndrome of the modern car was that it had become too well-engineered--too perfect. That the absence of flaws had robbed the relationship between the machine and its driver of its intrinsic give and take: ultimately making it an unfulfilling one. Simply stated, we love not in spite of flaws, but because of them.

I'll sign on to that. I do have a soft spot for the flawed. Especially the terminally flawed. The fundamentally and irrecoverably flawed.

Part of me is aware that this is probably the worst car I've ever owned. But I do like it anyway.